Poem 13

Success is as dangerous as failure.

Hope is as hollow as fear.

What does it mean that success is as dangerous as failure?

Whether you go up the ladder or down it,

your position is shaky.

When you stand with your two feet on the ground,

you will always keep your balance.

What does it mean that hope is as hollow as fear?

Hope and fear are both phantoms

that arise from thinking of the self.

When we don't see the self as self,

what do we have to fear?

See the world as your self.

Have faith in the way things are.

Love the world as your self;

then you can care for all things.

Reflections

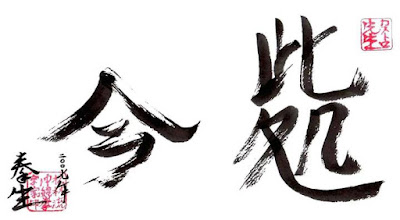

These poems from the Tao Te Ching are designed to make the reader or indeed listener (as in those ancient times when these lines were written oral cultures abounded, as only the very rich or people of status were able to read) think; to snap the person into a state of wakefulness or awareness. Koans, which can be in the form of a story, a question, a statement or even a dialogue, were traditionally used in Zen Buddhism to provoke the disciple into a deeper awareness or a keener sense of wakefulness than heretofore. In this way, the student's progress in Zen practice was tested. To my mind, the poems in the Tao Te Ching share in that purpose, namely to test and to deepen the student's progress in wisdom. The above poem is quite koanic (if this word exists) or koan-like in this regard.

Objectivity

All meditative practices allow us to withdraw a considerable distance from our own ego or from our obsession with self, from our egocentricity. If we can arrive at this stage of personal or spiritual development, we have become more objective about ourselves and are less likely on the one hand to swell up with pride when we are praised by another or on the other hand retreat in failure into gloomy despair when criticized. In that sense we can meet success and failure in our stride and not be too overcome in either an overly positive or overly negative sense. Another way of stating these objective sentiments would be by making the paradoxical or koanic statement that "success is a dangerous as failure." Once again, it's a question of not clinging onto or obsessively desiring those allurements or charms of the ego. In that sense, success can be dangerous to our discovering real happiness, which lies in discovering the real or true self that is hidden behind all the empty promises of our ego-ridden society. Failure can be crippling to the ego and reduce it to a state of not being able to do this or that. We want to keep the ego in a healthy place in our psyche, and we certainly don't want to cripple it. In fact, when we learn to give it its proper place in the psyche, balanced well astride the super-ego and id, then we can function confidently in life. We have to learn to be ruthlessly objective and never allow our failures to have any negative effect on our real and true selves. This takes some work in both personal development and on-going meditative practice to achieve.

Our Taoist poet tells us also that "hope can be as hollow as fear." In other words, the poet is telling us that unfounded fear or anxiety can reduce a person to an ineffective and passive on-looker rather than an active participant in society. Unfounded hope can be mere wishful thinking and lead us into despair.

Stanza three is pure koan and will only yield up a little of its wisdom after meditating upon it many times. Therefore, I am offering no explanation here, or attempted explanation even, as I have to humbly, like Socrates, admit my ignorance. What I will do is meditate and pray on it and leave it to the great Unconscious (or God, or Meaningfulness, or the spirit of life or whatever you wish to call it) to offer up some suggestive answer.

It is also my opinion that the Taoist poet uses the "self" in two differing ways in this poem. Stanza three seems to suggest that when we go beyond the self, or beyond being preoccupied or even concerned with self that it is only then that we have nothing to fear. Stanza four recommends, in a rather contradictory sense, that we must see all things in the world from the perspective of the self that it is only then that we can really love everything and everyone. This last stanza, then, is in the tradition of Jesus' famous command to his disciples to love their neighbour as themselves.

|

| John Keats: 1795 - 1821 |

However, as we all know by now, it is in the tradition of Taoist wisdom, as it is in that of Zen Buddhism, to hold the two opposites in a polar tension or union. Therefore, as readers of this beautiful Taoist poem, we are happy to remain in a state of what the famous ill-fated wonderful Romantic poet John Keats called "negative capability," a term he coined himself for the learnt ability in the human mind to balance opposites and hold them thus "without any irritable reaching after fact and reason." (see Negative Capability)

Conclusion:

One again, by way of conclusion, I invite the reader to read reflectively through the above Taoist lines and let a word or phrase spark a mantra for a five or ten minute meditation.

No comments:

Post a Comment